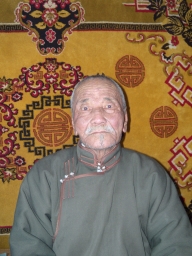

Gombo

Basic information

Interviewee ID: 990203

Name: Gombo

Parent's name: Tseveen

Ovog: Jambaldorj

Sex: m

Year of Birth: 1933

Ethnicity: Halh

Additional Information

Education: elementary

Notes on education:

Work: retired, was pensions bursar(?)

Belief: Buddhist

Born in: Gurvansaihan sum, Dundgovi aimag

Lives in: Songinohairhan sum (or part of UB), Ulaanbaatar aimag

Mother's profession: herder

Father's profession: herder

Themes for this interview are:

(Please click on a theme to see more interviews on that topic)

collectivization

environment

work

childhood

herding / livestock

military

Alternative keywords suggested by readers for this interview are: (Please click on a keyword to see more interviews, if any, on that topic)

Please click to read an English summary of this interview

Please click to read the Mongolian transcription of this interview

Translation:

Tsetsegjargal -

Will you introduce yourself?

Gombo -

OK, as things stand now?

Tsetsegjargal -

Tell us about your life.

Gombo -

Well, about my life. My parents brought me up. I grew up taking care of livestock. I joined the army in 1954. I served in the military in Ulaanbaatar for three years. After demobilization I worked as a senior agitator in a bag. Then in 1950, oh yes, in 1959 I joined the collective. I was a herder in the collective. I used to tend the livestock. I tended horses till 1963 and from 1963 I was responsible for bag, and then negdel, then brigade economy (aj ahui). From the that I was the agent then after that I was the veterinary nurse, then I was a vet in the Gurvansaihan brigade. Then I became a brigade darga, then I quit in 1975 to come to Ulaanbaatar, no, I went to Dundgovi. I had been a storekeeper at the administration of material technology provision in Dundgovi. I did it from 1975 to 1992. Then I retired. While retired I had a tailoring factory with ten workers in Dundgovi aimag. And lately it became close to bankruptcy and I couldn’t get the materiasl and technology therefore I came to Ulaanbaatar in 1995, you know. Well, there’s nothing special for a retired man like me, so I’m just doing a little bit of household work, you know.

Tsetsegjargal -

Let’s talk about collectivization. How did people join the collectives at that time?

Gombo -

Well, it was like that. At first in 1957, in 1956 it began, I think. A few families were united and the so called ‘valley collective’ was established. After that those small collectives were united into a big one. In other words, in 1959 officially the people were to join the collectives. So the first time we were to join the cooperatives what we were supposed to do? Because the country had livestock, one family was left with 150 head of livestock. Then in 1957, 1959, 1960 and 1962 it was again collectivized. The people’s livestock were collectivized again and again. At this second time one family was left with 75 head of livestock. So 75 head meant 25 head of large livestock and 50 head of small livestock which should be left. And within that if a family had more than 12 or 13 cows, one was to be collectivized. In fact, that’s how it was collectivized, you know. Then in 1959 with the victory of the collectivization movement, a few people might have slipped away to the city or to some other places, otherwise locally everyone joined the collective. That’s how it was collectivized. And we would tend the livestock and do various kinds of work. The aimag and sum cooperatives would give us cooperative duties and assignments which included cutting of the livestock hair and wool and we had to return it in full. For instance, one who tended camels had to give one sack of dried dung per camel, you know. If you failed to give the assigned dried dung some amount was withdrawn from your salary. The cooperative is… how to put it? Let’s say you get 200 or 300 tögrögs a month, 20 percent of it is withdrawn. It is not 20 percent withdrawn but it is left there, you know. The person who completed everything would be given that 20 percent. Let’s say, one had 2000 tögrögs left from his salary. If he completed all the milk, dried dung and wool assignments, he’d get those 2000 tögrögs. If he didn’t those 2000 tögrögs would be deducted plus he had to repay it. It was thus dangerous, you know. Yes. If you didn’t have vet’s certificate concerning the death of a cow, you had to pay it. For instance if a horse with a three-eyed chandmani brand died, you had to bring its skin to show and get approval, you know. So if the livestock died from age or disease, there were brigade vets who had to give a certificate of death, like ‘Gombo’s family bay horse died of old age and a three year old gelding died from disease.’ Only in this case would the costs be cancelled. Otherwise you had to repay it. In the recent years the large livestock weren’t used as much as the small livestock. The small livestock bones and wool would be used, you know. We had to bring their bones to cancel them from the list, you know. If we didn’t bring the bones, the bone cost would be withdrawn. That’s how the collectives were, you know. In recent years they had very strict rules and we had been in panic, in fact. Maybe in our homeland it wasn’t such, but such things happened everywhere. For instance, when one goat died it couldn’t be brought as a whole. We’d bring only his bones and they would be counted each. They used to take from us like that. Such were the collectives. Later, the failing collectives began in such a way. And in 1959 the remaining people were directly officially collectives. The first pretext of getting people to join the collective was that people began to be pressed with official wool and meat tax from the private livestock. People had to pay the livestock tax. They were oppressed in such a way. People had to give mutton instead of the horses. So they wouldn’t take horse meat instead of horses, but they took mutton instead of horse meat. For those who had horses they would use up their sheep, in fact. So people just couldn’t cope with all those duties and taxes. Yes. And it was understood they couldn’t go on like that. For instance, the livestock tax, it is still being talked about. If you fail to pay it, you have to pay a penalty and further interest would have to be paid. People even went to prison who failed to pay the official wool tax and the livestock tax, you know. That’s how it was, you know. You don’t know about it. You are completely unaware of it. So the collectives were like this, well those who somehow fulfilled their obligations, they lived fairly. And it was like this, you know, for those who tended the collective livestock, unless the brigade darga or the sum darga signed the paper that family wouldn’t make a fresh meat soup if someone in the family had delivered a baby, you know, for they didn’t have their own livestock. Those who tended the collective livestock they didn’t have their own livestock and most of them didn’t have a horse to ride, you know. They always took care of others’ livestock. That’s what the collective was like actually. Yes. That’s what I can tell about the collective s, you know.

Tsetsegjargal -

How did the individuals join the collective?

Gombo -

When the individuals joined the collective they had to attend the collective meeting. Those who previously established the collective would come to the meeting, you know. The members would negotiate whether to take this Gombo to join the cooperative or not. Then deciding to let him join it, the members would raise their hands and approve. And he would say he had this many livestock and this many livestock would be nationalized and so on. For instance, if he had 150 head of livestock, or if he had 250 head of livestock, 100 head of livestock he would collectivize. Then in the process of collectivization he would say he would give this many horses, this many camels and this many sheep and all this would be signed and they would drive the livestock to the ail. That’s, in fact, how it was actually. In order to become a collective member one had to be sixteen years old. Thus one joined and became a collective member. After becoming a collective member he had the right to take part in all the collective’s activities. Once you reached sixteen you joined the collective. There was no upper age limit for that. It didn’t matter if you were 70, 80, 90 or a hundred years old, once you joined it, it was OK. If the herders worked well the collective would certify it by giving out anniversary medals and so on. Men used to retire at the age of 60 and women at the age of 55. The 60 year anniversary of the elderly men who herded the livestock reasonably well would be celebrated. Some measures were organized at Mongolian tsagaan sar. If you ask questions I will answer if I know it. The collective was like that. Those who herded the collective livestock were given two or three horses from the brigade darga as transportation. They would use them for tending the livestock, and what else they would do with them? People didn’t keep large livestock for living purposes. They would rather keep small livestock for their food therefore there were many families that didn’t have transportation livestock It was all given from the collective. Some would ride camels and the others would ride horses and the camels were given from the camel stock and the horses were given from the horses stock, you know. That’s how we lived.

There wasn’t any compulsion to join the collective. It wasn’t necessarily required to give a certain number of livestock to join the collective. It was very mild in the beginning, you know. In other words, it was the method of joining and involving people into the collective, right? If one was to join the collective with 150 head of livestock, he was to give the percentage from the livestock, you know. And those who had many livestock they remained with 150 heads of livestock. That’s how the collective was.

Tsetsegjargal -

How did people accept the collectivizaton?

Gombo -

At the beginning, you know, people were exempted from tax and other official livestock taxes, therefore people joined. But later people wouldn’t join it. In 1959, in fact, delegates from the aimag, city and sum would come and insist and push. And later everyone was required to join it so in 1959 everyone was included. So 1959 year is said to be the year when the forming of the collectives was completely fulfilled. You ask the questions, and I…. People who couldn’t fulfill the requirements they wouldn’t join it, you know. For instance, let’s say there’s a family with 100 horses, 150 sheep and several goats. They had to give meat according to the number of sheep, right? Mutton was supposed to be given for the horses. In such a way people had no livestock, you know. People couldn’t cope with the taxes therefore they weren’t so eager to join it, but those who had many livestock were the first to join the collectives, in fact. Right? So the first time those who could pay the livestock taxes joined it. There was a sum collective darga during this collectivization time. There was one bag of people who didn’t join the collectives. Actually it used to be called a brigade. After the collectives it was called collective brigade and earlier it was called a bag. It used to be said that the sum had this many bags. Nowadays we say the same thing, the sum has this many bags. That’s how it began, you know.

Those who were reluctant were left and they were later officially pushed to join in. There were few people who were reluctant, many people couldn’t do so, you know. Only few would be. There were actually quite many but some later joined under the pressure though they were reluctant to do so. Those who were a little cunning and bright they sold their livestock and wasted the money and cleared off to the city. That’s what they did (laughs). Otherwise if you stay in your valley herding your livestock you couldn’t stay away from that collective. Well, it is considered that the collectivization was carried out officially and in 1959 all those who were left out were made to join it.

Tsetsegjargal -

What happened during the collectivization movement?

Gombo -

You mean at the beginning? At the beginning, in general, you know the transportation and airag and milk, everyone observed the living standard and you see… At first the poor people, those who had no property, joined the collective. The poor people first and later one or two well off people joined with their livestock. Then they began to divide the livestock. After that those who couldn’t fulfill the official assignments were exempted from their official assignments by the collective and they just gave away their livestock and joined it. That’s it. Regarding those who could fulfill the official assignments, they didn’t want to join the collective under the pretext that they could cope by their own, you know. And in 1959 by official agitation and propaganda they could nothing other than to join it. That’s how it was. And you know what? At the beginning of the collectivization, people were exempted from the official tax assignments and they could live well with their 150 heads of livestock. But the repeated collectivization meant people were left with almost nothing. That’s how they tied them.

Tsetsegjargal -

Did the herders conceal their livestock during the collectivization movement?

Gombo -

Well, they didn’t conceal it. In fact, they didn’t conceal it at all. They stood there as it was. But it was like some said they would give and the others said they wouldn’t give. Otherwise why did they have a grudge when joining the collective? At first people voluntarily collectivized their livestock and by the end, just as I said, they would divide 75 head of livestock and they would leave their share. As I said, from 75 head of livestock 25 were large livestock and 50 small livestock. If you didn’t have 25 large livestock and all 75 were small livestock, it was OK. And the large livestock had to be 25 or less.. There could be no more than 12 cows. If you had 13 cows one of them had to be collectivized. That’s how they made it. Yes. And in fact it was prohibited to have 75 heads of large livestock for a family. It had to be only small livestock. Maybe they feared that they would have many large livestock? But when the government once again collectivized the livestock after making people join the collective, people probably concealed their livestock. Perhaps there were few people who followed the rules strictly. That’s generally how it was. There wasn’t any of that kind of concealing at that time. But in the olden times, like it is shown in the movies, people concealed their livestock. Such things happened, you know. Otherwise, during the collective period people didn’t conceal their livestock. My god, what do you mean conceal?! The estimations were conducted very thoroughly in the countryside, you know. A group of people would be organized for an estimation commission. And that group of people would visit, let’s say, Gombo’s today and they would stay overnight there and begin counting the next day. The estimation began on December 15th and it was such a rule nationwide. So today they’d visit Gombo’s, another day Dorj’s and so on. They had such a route. And by the same route there would be an auditing from the sum, then from the aimag and even from the state. The collective livestock would be counted in a line and the private livestock would be counted tied up. It was so thorough. They’d tie up the livestock and would count the age of the livestock, you know. Yes.

Tsetsegjargal -

Were there articles published in the press about the collectivization movement?

Gombo -

Well, there was a radio station called ‘home country 52’ at that time. There were very few of them. They would speak on that radio. Well, in the sum and aimag they said the collective was for the benefit of our life, to enhance our living conditions and so on. People from the aimag would come and hassle those didn’t join the collective. They would meet with those people and instruct them. ‘You should do this and this. You are going out of line and this is a state policy…’ That’s what they said. It was really pushed and required to join the collective. At the beginning there was no pressure and there was a lot of propaganda. One would lead this work and 17-18 families from one location joined and established the first cooperation, you know. There were 4-5 collectives in one sum, for instance, in Gurvansaihan sum. Then with another collectivization of livestock all those collectives were bound into one large collective. That’s how it was. What else did you ask me? The collective will enhance your living condition, and the official rules were really serious, you know. And those official assignments of meat and wool had to be paid in an official way, you know. And you give this much mutton, this much goat meat, this much horse meat. So everything is given away. And there would be no poor commoner so, let’s join the cooperative and work like one family. It was written a lot in such a way, in fact.

Tsetsegjargal -

In the newspaper?

Gombo -

Yes, it was written. It had to be written at that time. They used to write a lot. Such and such collectives were formed and they work well, such things were talked about a lot.

Tsetsegjargal -

Did certain groups of people talk about the forming of collectives?

Gombo -

Well, you know, in fact, people came from sums and aimags to talk. There was one senior agitator (propagandist / activist) in one bag. There used to be also two or three family agitators. They used to introduce people with the directions given from the press or the aimag party committee actually.

Tsetsegjargal -

What did they talk about exactly during the collectivization period?

Gombo -

Well, what could they talk about? Generally they agitated to form the collectives, right? The collective is this good and the collective has these nice living conditions and there will be no poor people, everybody will have an equal life, right? But at that time there were many poor people, you know. They were poor without livestock and they were nearly beggars. Once they joined the collective and worked well those who were poor and had no belongings, in fact, recovered. They were the people who had no private belongings, who had no money or salary, you know. So in the collective they worked and they got their labor payment or salary, you know. In such a way his living condition was enhanced. A lot of propaganda was made that this family was in such a condition and now it had become like this, you know. In fact, it was the government policy that the people should live together and that it is the real issue. Therefore, it is right for you to join it. You shouldn’t stay away from the collective. That’s what the agitators talked about. They introduced people to the latest news and they introduced people with meetings and consulting meetings that were held, you know. We used to have bag meetings at that time, right? Delegates from the aimag and sums came and the bag members and the agitator were there. People mostly talked about the collectivization movement at those bag meetings. You should do this, people were encouraged to join cooperative without losing time and people understood well. That’s why most of them joined it. But the last few people had always made excuses not to join and in 1959 groups of people from the aimag and sum came pushing and demanding and due to this they had to accept the collectivization movement, you know. Those who were reluctant, they observed the collective members who had very few belongings. They had only 75 or 150 head of livestock. So in fact, those who fulfilled the official tax assignments, they observed that joining the collective they would lose their property and that’s why they struggled against it, you know. There was no other reason, right? In other words, the state confiscated their property, right? Right. So they didn’t want their property to be confiscated and they struggled for their private property, just like we have today. When it was clear that there was no other way for those who had livestock, those who had a trading business at that time, they sold their livestock or exchanged it for something else and left somewhere. There were few such people. There weren’t so many of them. And there was no other way for them, but to join the collective. In the last years the official tax assignments were increased and there was too much pressure and demand, so people just couldn’t cope with it, you know. So the reason was they couldn’t cope with the official tax assignments. That’s how it was. Before the second collectivization it was quite fair and people got their salary in full. When the collective livestock numbers increase and it has great income the collective becomes fully independent financially. In fact that’s what happened. The collective had plenty of capital, it had a lot of money in the account and it what you call it various types of what you call it to people. It, what you call it, all those labor payment, the awards and the incentives. With the increase of the income it became so. And in the later years the herders were not so good, they couldn’t cope with the livestock. You know, let’s say two herders had almost 1000 head of livestock. At the end they couldn’t cope with the livestock, the strength of people weakened and the young people generally left the collective to study in bigger places. Herders became rare, you know. That’s how we lived and actually after the democracy in 1990 and the privatization… generally many people obtained livestock. Those who worked in the local sum and who herded the livestock received the privatized livestock. The livestock were privatized by a number of people. The large families who had many children obtained many livestock, you know, by the privatization. Just think, at that time there were herders with thousands of livestock everywhere, you know. It was confiscated. And the people were given some livestock for food. Of course, it was given very cheaply. Some would take 5, the other would take 10. People took a lot of it. Sometimes it was given in single files. The old livestock were slaughtered. The foul ones were separated in one special place and they were brought to the sum center to be slaughtered and given to people for its cost. The collective household had plenty of meat so it didn’t need it. There was no hunger so it managed to provide people with food and drink. But the last years it was a little panicked for it couldn’t manage the livestock. The herders were the people who tended livestock for many years and those herders grew old nationwide. The herders grew old and the youngsters withdrew from the cooperatives to study. They didn’t withdraw from the collective because they were hungry or because they didn’t get salary, you know. Perhaps they just exercised caution on those high taxes and those strict assignments. The living condition of the people pretty much changed compared to the past when there were only few rich people, you know. Certainly, everyone’s life changed for the better. In fact, it improved a lot. Since people cooperated to do any kind of work, for instance, we used to cut the livestock’s wool or comb it together in cooperation, you know, once the collective property was the public property. Therefore the living condition was quite fair. Just taking the example of our homeland life, due to the mismanagement of the livestock there was a lot of loss from it. The only thing was that livestock almost stopped growing, otherwise we were never hungry. Those who did work well, in fact, their lives prospered. Generally, after joining the cooperative the living condition didn’t get worse than the previous life in a bag or brigade. When we lived in a bag or brigade we only had 5 tögrögs for the livestock wool or horsehair trade and nothing else, you know. So, in the cooperative everyone had a salary. That’s why their living conditions were enhanced. You can’t say it was deteriorated. By the end the herders grew scarce, therefore there were many livestock losses and the profit decreased mostly due to the deterioration of the herders’ ability. Well, some of them withdrew in various ways to get education, it was even reflected in the movies, you know. Such things used to happen in the olden times, you know. That’s what it was. And also the livestock and the property of the people increased by the end. With very few herders many livestock were concentrated on two people hence they couldn’t fulfill the assignments and duties. That’s was the only problem. Yes.

There were few people in the office. The collective had one darga, one accountant and one housekeeper and that’s how it began with few people, you know. Only in the recent years all the collectives were banked up and it grew big. Well, even the small collectives banked up all the horses that came from the people and formed two or three places and put the horse herders in charge. But the sheep and goats weren’t separated. Actually the sheep and goat place was separated like pregnant animals, the non-pregnant animals and one-two year old livestock, you know. The previous year one-two year old livestock was separated this year like non-pregnant, the females were separated like ewe-lamb and the males were shifted to the sheep and goat place. Then the one-two year old female livestock and the one-two year old male livestock and the sheep and pregnant goats were separated. That’s how they were separated, you know. And the female camels, you know, were separated like preganant female camels and the barren female camels place. One person was in charge of calving 30 female camels and three people were in charge of calving 90 female camels. Then they had to shift them to the corresponding places, you know. There was the cows place and the horses place, right? The one-two year old livestock are separated by females and males. That’s how the herders actually separated the livestock. Well, the herders’ movement gave gers and allowances to the poor herders. Certainly, the collectives worked for the good of people. If you ask about the recent period, then there is one sum collective darga with one collective deputy and one sum deputy. Then there was a massive collective enterprise (aj ahui) and the collective deputy was in charge of that enterprise. The enterprise meant organising the building construction materials, the dairy products and meat and milk and it distributed it all. We used to go to the collective and buy the dairy products and eat it sparing no money. At the beginning there was plenty of everything. Then later the livestock deteriorated actually and people became inactive. In the beginning it was very good. It was a time when dairy products, the fat and dried curds were put up, you know. Besides tending the livestock there were other activities like furnishing the collective center and in the later years the so called assisting brigade was formed from many skilled craftsmen who worked with wood and iron and they used to build constructions in the collectives. They used to do all the work of the collective. They built additional office constructions or store houses for the brigade and sum. If you joined the collective it would give you transportation. We used to move by the collective transportation. That’s how it was. The collective transportation, the collective vehicles and so on and the collective itself were all government property, you know. The livestock that were sold were taken by truck or tractor. The tractors were given for the haymaking and fertilization in the mountainous areas. Young people were made to do the haymaking for some time and later the collective fetched it. They fetched it and the fodder was sufficient at that time, you know. The fodder, the fodder grass and so on was cast down by several trucks. Certainly everything was sufficient at that time the only thing was that they couldn’t cope with it. And when the families moved in the springtime there, unused fodder grass was left in their courtyard. There was a lack of care, you know, and the fodder grass was decomposed and it had to be thrown away.

Tsetsegjargal -

What event had a great impact in your life?

Gombo -

For a living? Well, what influenced… well, we had our own property and we coped thanks to it and later when we became cooperated there was nothing that we lacked, you know. There was nothing special with regard to impact. I have no complaint about it not having an influence on me and the like. Generally the collective took care of us at that certain time. What did influence my life, was when I was a treasurer of the provisions, my living condition enhanced greatly compared to the cooperative period. I didn’t mean to quit being a member of the collective. I just came to the aimag center and worked for many years in the provisions. I didn’t go into debt and many times I became the organization champion. And all those organization anniversary medals and the shock worker and so on I received only here, you know. I hadn’t received any of it in the collective. In fact, I have many state awards. I have the complete five year shock worker awards. I got them all here. Yes. I got the 1960 year shock worker award, the organization champion I received many times. All the state awards and prizes I got only here at the material provisions, you know. Yes. I worked a lot in the countryside. And I worked a lot in the collective. But, well, actually I got plenty of it. I wouldn’t say I worked not well. I was generally OK by individual what you call it. I used to fulfill everything on time wherever I worked. I looked after the enterprise and the agent in the brigade. I was the vet and the brigade darga. Actually I did everything. I wasn’t involved in any kind of a conflict and I didn’t go into debt. I always strived for the work like people would say, I was a workaholic. I strived for it faithfully. Actually it was my parents’ and also the state moral. There are some people who have the wrong attitude towards public property, those who waste things, you know. I wasn’t of that kind. Actually I abstained from it all. So, one pack of matches cost 10 möngös and I was a treasurer of the organization that had a 27 million tögrögs turn-over. I had one assistant. Yes, I had one assistant. Isn’t it a lot money for that time? Yes, it is. The material provisions took good care of me. And the collective did nothing to make me say it didn’t take care of me. I was never talked of actually as a bad worker.

Tsetsegjargal -

Is there anything unique or special in your life?

Gombo -

What could I have that is anything special? I haven’t anything unique in my life, actually. What could it be? I have little education. I haven’t acquired much knowledge, in fact. Yes. But I’m fully satisfied with my life. Actually I served well for three years in the people’s army. I got awards and I spent three years in the army. When I served in the army the agricultural institute building was handed over. Colonel Byambaa, the merited constructor who was awarded the Labor Hero order was the chief of our military unit. There was a big Construction battalion here, you know. When in December of 1957 the Agricultural Institute was handed over, it was the biggest construction nationwide, you know. What it is like when you look at it now? (laughs) I have no greediness, you know, to distinguish from others. I don’t think of taking something from someone or cheating. When I was the treasurer of this big state organization that had great capital I never thought of taking from it. That’s what I actually think. I don’t know how people judge. In my own opinion I worked for this state as earnestly as I could. There’s nothing else I could be wrong about. Actually I have nothing of a flattering or selfish disposition. I thought of only work, you know. And I consider the present day youth as a bit irresponsible and weak, you know. (laughs) Yes.

Tsetsegjargal -

How did the natural environment change in your homeland?

Gombo -

The change of the present environment…in recent years there has been no rain in my homeland, that’s the big change. Since 2002 the weather in my homeland has not improved, you know. You know, our sum moved to the Herlen bank, to this Töv aimag and to the north-west of the Ar and Övörhangai, you know. Only last year most of us gathered from the last autumn. People have ceased to stay in our homeland, you know. In fact, there’s no ill feeling, you know. There are only several people in the sum center, some schoolchildren and mostly old people and some state officials there. There’s nothing else, in fact. The people of my homeland have vanished, you know. It has deteriorated immensely, you know. Since we stopped having rain. I don’t know what will happen this year. This autumn there was a little rain and some wild leek appeared here and there. Otherwise in the olden times it was wonderful. We had a lot of rain and nobody moved anywhere because of lack of precipitation. People from my nutag moved even to Övörhangai, actually. And then to Herlen bank, this Choir, this Baganuur, Maanit, in fact, people had all stayed here and now they are going back, you know. Yes, and that’s the changes we have. There are quite a lot of changes regarding nature and weather in our place. Well, it is a very memorable wonderful place and people visit a lot, people call this place Ih gazrin chuluu. That stone is of our homeland. It is our homeland. It is situated in 20 km from our sum. In fact, it’s a tourist place, you know. It has a tourist camp and well, such is that place.

Tsetsegjargal -

What were the positive changes in the nature and the weather of your homeland?

Gombo -

There isn’t such a specific positive change, in fact. Actually it has a normal wonderful weather. Because the land is in the Gobi territory the mountains are beautiful. It’s a beautiful Gobi land, you know. The southern part is Gobi land and the northern part is mountainous land, in fact. There isn’t specific change there. Recently the weather had deteriorated and there has been no rain, so people have begun to move quite often.

Tsetsegjargal -

What are the negative changes in the nature and the weather?

Gombo -

Well, it has become a place of dusty storms, you know. Actually there’s a lot of dust and sand. In fact, this place turns into arid desert, you know. I would say so. Yes. It seems to be turning into desert. Actually it wasn’t like this before. Now it has become like this.

Tsetsegjargal -

Had the names of land and rivers changed in your homeland?

Gombo -

I don’t think the names of lands and rivers changed. In fact we didn’t have places that had names before. Historically, Dundgovi was founded in nineteen forty something, you know. In fact, Dundgovi aimag was founded by the sums that were separated from Dornogovi, Ömnögovi, Övörhangai and Töv. Otherwise, there’s nothing else special. And it is still the same. Our sum is called the eastern Gurvansaikhan sum of Ömnögovi, you know. It was affiliated to Ömnögovi before and later it separated. And you know the western Gurvansaihan, you know. You know, people talk of the beautiful places of our Govi Gurvansaihan. And Ömnögovi used to have three beautiful places. The eastern Gurvansaihan was our place. Then Dundgovi aimag was separated. That’s what you call it… Then there was Buyant sum from Ömnögovi and it was abolished. Buyant, Ölziit, Delger Hangai, Huld, Luus all these sums had come from Ömnögovi. Then Bayanjargalan, govi what… yes, Bayanjargalan, Öndörshil came from Dornogovi. Govi-Ugtaal, Tsagaandelger, Deren, Adaatsag they all came from the Töv aimag affiliation. Saihan Ovoo and Erdenedalai sums came from Övörhangai. That’s how it was founded, you know. Then at the Zuugiin Khar-Ovoo foothill Dundgovi was founded. That’s it. Yes. We don’t have any serious changes like digging gold and ore somewhere and making a mess out of the land. But there are some places in our homeland where spar (a mineral) or what you call it, is being dug. Otherwise, we don’t say, it’s because of this it happened. I think it’s just necessary things happening there and there’s nothing like ‘this place was dug and the water was spoilt and because of it we have this’ thing. There’s nothing of that kind. Everything is going naturally, in fact.

Tsetsegjargal -

Thank you for your interesting interview.

Gombo -

Well, it’s OK if I’m doing well in this interview. I have a herders’ origin, I grew up in a livestock husbandry. I have no education. That’s it, actually. I was born in June 10th, 1933 in Bayanbulag foothill of Tsolmon slope of the eastern Gurvansaihan sum of the former Ömnögovi aimag. I was brought up by my parents and at six-seven years of age I tended lambs and at ten years of age I tended sheep and collected dried dung and helped with the household work. I haven’t studied at school. I didn’t go to school, but I copied the 35 letters of the alphabet from the children who went to school. That’s how I became literate. I found out from them that 9 of the 35 letters were non-vocal, 4 – extra, 2- signs, 20 – consonants, 7-vowels. I divided the letters and learnt by myself and learnt to read. Since then I joined the army in 1954 and I served in the construction command at colonel Byambaa’s unit, the 64th construction unit, till 1957. Our construction command was a very large command with three battalions. Then what was it, I forget. Yes, the command chief was colonel Byambaa. The commander of the staff was the deputy colonel Baadai, political assistant was the deputy colonel Mejid. The commander of the staff the deputy colonel Baadai had a patriotic rank of a Halhin Gol and he was from Ulaanbadrah sum of Ömnögovi. I served in the people’s army till the end of 1957. In 1954 for one year I was a soldier and from 1955 to 1957 I worked as a commander of a squad with a rank of sergeant. Later our squad became the construction, no… the guard squad and I had worked as a guard director for over a year. Then I was demobilized in 1957 and worked as a herder and joined the cooperative in 1959. From 1957… from 1959 till 1962 I worked as a horse herder, in 1962-63 as a sheep herder and from 1963 I worked as a brigade household agent and vet and the brigade darga till 1975. From 1975 till 1992 I worked as a senior treasurer at the construction storehouse of the material technical provisions administration of Dundgovi aimag. In 1992 I retired and I worked at the tailoring workshop of the public service. In 1995 I came to Ulaanbaatar city. I lived in 11th horoo of the Bayangol district and moved from there to the 3rd horoo of the Songinohairhan district and I still live there.

Interviews, transcriptions and translations provided by The Oral History of Twentieth Century Mongolia, University of Cambridge. Please acknowledge the source of materials in any publications or presentations that use them.